By: Malaika Mathew Chawla

The largest ongoing protest in the history of humanity, occurring amid a global health emergency, revolves around small-scale agriculture, farmer rights and democracy in India.

Hundreds of thousands of farmers and labourers in India have been protesting three newly introduced farm laws since November of last year. While farmers mobilise and rally throughout the country, the most significant ones are the camps and tractors set up at New Delhi’s outskirts. An entire season has gone by. Chilling cold winds are replaced by hot, mosquito-filled summer nights. Alongside this, the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has hit India. It is deadlier and even more heart-breaking. Still, farmer unions stand by their decision to continue their protests: “If the government was so worried about Covid, why did they introduce such significant agricultural laws during the pandemic?”

Photo source: Twitter/@Kisanektamorcha

“If the government was so worried about Covid, why did they introduce such significant agricultural laws during the pandemic?”

It’s telling that the biggest killer of protesting farmers is not the virus. Since the beginning of the agitation, 370 farmers have died at protest sites or while travelling to these sites, with reasons including suicide, heart ailments and harsh weather. They endure extreme weather conditions, police brutality and now the second wave of the coronavirus. It is important to remember that the agitation only reflects a systemic failure to address India’s deep-rooted agricultural crisis.

Volunteer-run organisations like Khalsa Aid have been supporting protesting farmers by building makeshift shelters, food relief and first aid centres in Delhi. The organisation has also ensured that farmers do not run out of essentials like mattresses, blankets, and personal hygiene products. A langar (free, community kitchen) is organised every day at the protest sites for everyone present. In the bottom left and bottom right photos, the author’s mother prepares lunch with other volunteers at a langar in Mumbai. (Top left photo: Twitter/@Kisanektamorcha; top right photo: Twitter/@khalsaaid_india)

Volunteer-run organisations like Khalsa Aid have been supporting protesting farmers by building makeshift shelters, food relief and first aid centres in Delhi. The organisation has also ensured that farmers do not run out of essentials like mattresses, blankets, and personal hygiene products. A langar (free, community kitchen) is organised every day at the protest sites for everyone present. In the bottom left and bottom right photos, the author’s mother prepares lunch with other volunteers at a langar in Mumbai. (Top left photo: Twitter/@Kisanektamorcha; top right photo: Twitter/@khalsaaid_india)

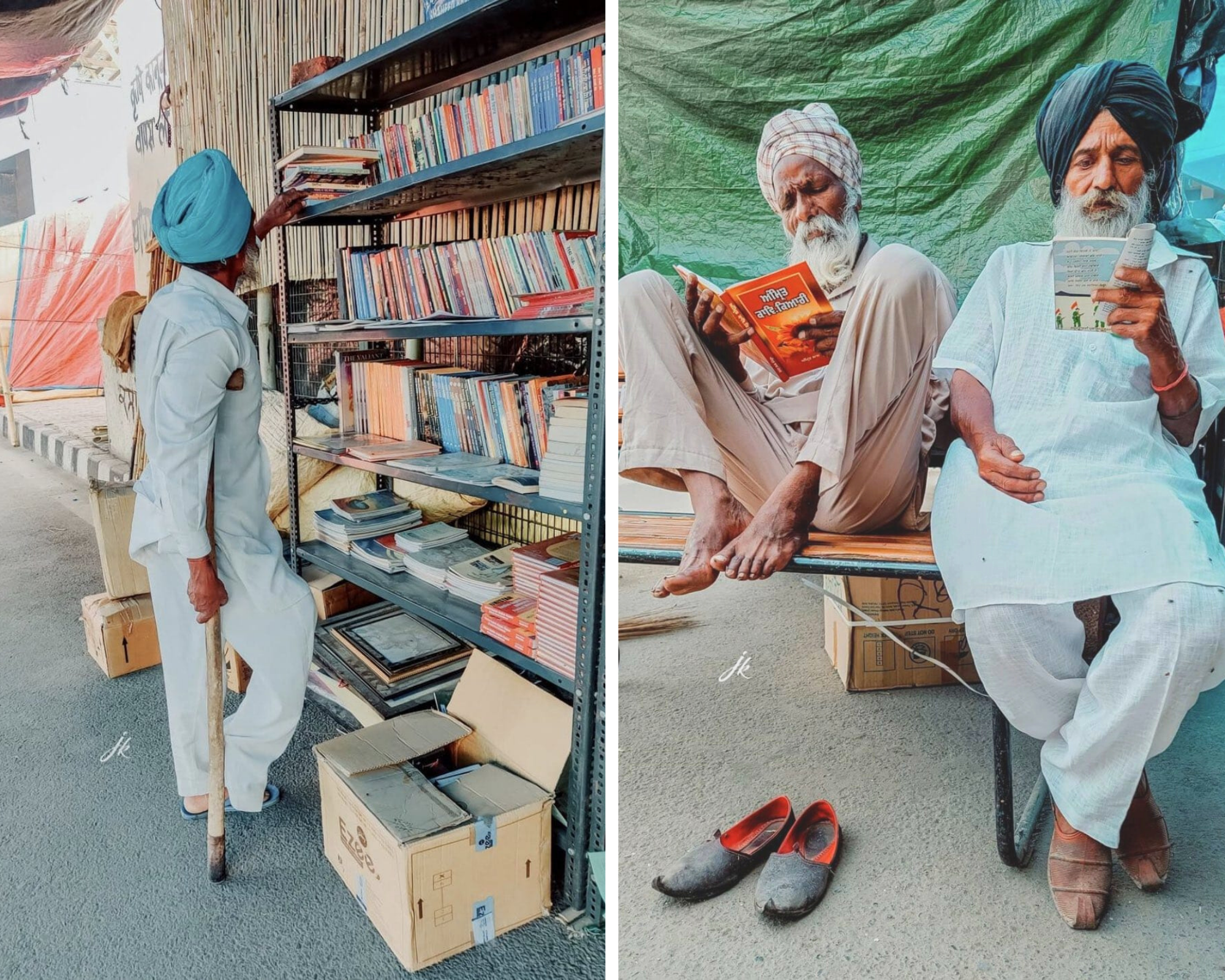

Makeshift libraries have been set up at protest sites in Delhi’s borders. Volunteers also use these spaces as schools where they teach disadvantaged children. (Photo: Twitter/ManiChander11)

Not safeguarding the farmer’s fair price is yet another blow

Before we attempt to understand why farmers are protesting, let us take a look at a few numbers about agriculture, food security and inequality in India.

- Farmers make up 60% of India’s population with small and marginal farmers making up 85% of the farming population (Down to Earth).

- The average Indian farming household (may consist of up to 5 people) earns Rs 6,427 a month which converts to AUD 111.20 (Situation Assessment Survey of Agricultural Household 2013).

- Agricultural daily wages have been steadily declining since 2017 (Reserve Bank of India).

- In 2019, 28 people dependent on farming died by suicide each day. According to government numbers, 10,281 people died in total (National Crime Records Bureau).

- 85% of rural women are agricultural workers, yet only about 13% of these women own land (Oxfam).

- Rural women produce about 60-80% of India’s food (Oxfam).

- A survey conducted in 2013 found that among 5000 farming households in India, a majority said that they would give up farming if they could (Centre for Developing Studies).

- Punjab and Haryana, also known as India’s grain bowl states, are among those regions in the world facing severe water shortages. In both states, most of the water is used to irrigate paddy and wheat fields (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

- India ranks 94 out of 107 countries in the Global Hunger Index 2020.

- During the first Covid-19 lockdown in India, an estimated 400 million Indians lost their sources of income, further pushing them into poverty. There is no publicly available government data about deaths due to starvation during lockdown, but numbers are said to be high (The Telegraph).

- More than 300 migrant workers died during the first Covid-19 lockdown, with reasons including starvation (Oxfam).

- The richest 1% Indians possess four times the wealth of the poorest 70% of the country’s population (Oxfam).

The Farm Bills

In September 2020, the Indian government passed three farm bills that would institute some of the most sweeping changes to agriculture in decades–without any consultation with farmer groups and other stakeholders. While the government claims that the laws will free farmers from their present misery, farmers counter that the laws completely threaten their livelihoods.

The first law allows farmers to sell their produce outside of government-regulated markets and directly sell to private companies, including big agri-businesses and supermarkets. The second law allows for farmers to enter into contracts with buyers like retailers before production even begins. The third law removes certain crops like cereals and pulses from the list of essential commodities and removes stocking limits on these crops.

For several years now, the Indian government has offered guaranteed minimum prices to farmers for certain crops. Some of these crops are wheat, paddy, maize, barley, chickpea, lentil, soyabean, sugarcane and cotton. This price is known as the Minimum Support Price (MSP). Simply put, the MSP is very much like a minimum wage. The MSP ensures that the farmer makes a minimum profit for their harvest. Now, the heart of the matter is that the MSP is not legally enforced. Ensuring that the farmer is paid at least the MSP is just a government recommendation, not the law. The biggest fear among farmers is that the three laws will lead to the scrapping of the Minimum Support Price.

Farmers also fear that India’s most marginalized rural communities will be worst hit. We already know that most of India’s farmers are marginal to small farmers. A marginal farmer has up to 1 hectare of agricultural land while a small farmer has 1 to 2 hectares. This compares to a large land holding of over 10 hectares. Such small landholdings stem from historical oppression through India’s caste system. The stark reality is that a majority of farmers belonging to lower caste groups hold small and marginal land. The land is so small that the farmer gains little to no profit. Additionally, profits also depend on a multitude of factors like weather, access to water and electricity, capital, crop insurance and access to information.

Let us imagine that a small farmer is ready to sell their produce. The farmer takes their produce to a government-run market, regulated by the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act. These markets are known as APMCs or mandis. If farmers are unable to negotiate a price with licensed intermediary traders, the government will buy the produce instead. This purchase is made at the Minimum Support Price. Therefore, the MSP ensures that the farmer gets at least some money for their produce.

Now with the roll out of the new laws, the farmer will have the option to directly sell their produce to supermarkets, food processing companies and other private businesses, in the absence of intermediaries. Outside of government-regulated markets, the farmer will most likely be exploited by big corporate agri-businesses and may be denied a fair price. The issue of the Minimum Support Price, which lies at the heart of the protests, is not directly referred to in the three new laws. However, farmers fear that getting rid of government-regulated markets will facilitate the scrapping of the Minimum Support Price. Instead, farmers have demanded that the government pass a law that makes MSP a legal right.

While this article hopes to provide a simple understanding of the Minimum Support Price, readers are encouraged to dig deeper and read about other criticisms that the new laws have garnered, how the Indian government has responded to the protests and the demands that farmers have made to the government. A failure to protect the farmer’s fair price will only deepen the divide and further marginalize an already marginalized community.

India’s women farmers on the cover of the American magazine- TIME, in the March 2021 edition. Read the cover story here. Photo: Twitter/@TIME

Resources:

- https://time.com/5942125/women-india-farmers-protests/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/5/100-days-and-248-deaths-later-indian-farmers-remain-determined

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-55413499

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/04/13/india-farmers-protest-punjab-haryana-modi-water-crisis-climate-change/

- https://thewire.in/agriculture/indias-farmers-protests-guide-issues-at-stake-reforms-laws-msp

- https://www.newslaundry.com/2020/12/04/why-landless-and-marginal-farmers-are-the-backbone-of-farmer-protests

- https://sabrangindia.in/article/against-farmers-dignity-right-fair-livelihood

Donate to Khalsa Aid to help protesting farmers here

A record of Indian farmer deaths during the protests, maintained by protestors themselves here

About the Author

Malaika Mathew Chawla currently works as a Produce Packer with the Melbourne Food Hub. She is deeply passionate about biodiversity conservation, environmental justice, and local food systems. She has recently graduated with a degree in Tropical Biology and Conservation. She hopes that her work and her writing will highlight how our food problems and our environment problems are deeply-interconnected issues. She spends her free time staring at gum trees and drawing them. She also likes to read and learn about Australia’s indigenous history.

Recent Comments