While the coronavirus pandemic has been the focus of our news cycle and public conversation for the past couple of months, it’s hard to forget that just before that, our nation was devastated by months of unprecedented, climate change-fuelled bushfires which were made much worse by the preceding long periods of drought in many regions. In many ways, the past six months have been defined by crises, and have left many of us wondering how best to move forward in such turbulent times.

If the past few months have shown us anything, it’s how precarious our supply chains are in times of crisis. From food and water shortages in bushfire affected regions over Summer, to scenes of empty supermarket shelves across the country during the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, it has become glaringly obvious that our current food system is insufficient in meeting our needs in challenging times; whether they be environmental, social or other.

This awareness has led to a boom in interest in home food production, as people are coming to realise the important role this has to play in growing localised, resilient food systems. Our three part article series ‘Cultivating Resilience: A Beginners Guide to Home Food Production’ provided some guidance for those just starting their journey in gardening, covering the basics necessary to get growing.

However, the unique challenges posed by climate change require us to delve a little bit deeper, and cultivate an adaptability in our gardening practices like never before. This article aims to do exactly that: explore the ways that climate change is impacting food production, and to look at ways we can both mitigate, and adapt to these challenges in our own backyards or community gardens so we can keep growing food now, and into the future. Bear with us, this next part is a bit heavy, but we’ve got to understand the issues before we can explore the solutions (of which there are many!)

The challenges of food production in a changing climate

Predictions for how climate change will affect the weather and therefore our food systems vary depending on your region. Here in Victoria, the current predictions are:

– Temperature: Average temperatures are expected to continue to increase year-round, with longer and more severe heat waves becoming more common. Prolonged periods of intense heat can cause heat stress and sunburn to plants, lead to premature bolting (plants finishing their life cycle sooner than they should); wilting due to increased evaporation and loss of soil moisture, and reduced yields, to name a few.

Warmer winters mean less frost, which could have the benefit of lengthening the growing season, and allowing spring planting to take place earlier. However, some crops like apples and stone fruit require a certain amount of cold days to set fruit, and could be negatively affected by warmer winters. There are also many pest insects that currently go dormant in Winter which may be able to remain active over this time in the future, leading to increased pest issues in the garden.

– Rainfall: Droughts are expected to increase in occurrence and severity across much of Australia, with less rainfall predicted for autumn, winter and spring. Meanwhile, extreme rainfall events (heavy downpours in a short period of time) are expected to increase, which makes capturing and storing rainwater more difficult than with more regular but less intense rainfall. As most veggies need regular watering to produce well, increased water scarcity will be a big challenge moving forwards, as will the potential for flooding and waterlogging in the case of heavy rainfall in the wrong part of the growing season for some crops.

– Bushfires: The combination of increasing droughts, heatwaves, extreme storm events and degraded, mismanaged forests will continue to pose huge threats into the future, with the bushfire season expected to increase in duration and severity. Fires have obvious impacts upon food production, supply chains and distribution, with rural farms being particularly at risk.

– Pollinators: Changing temperatures are resulting in plants flowering at different times than they have in the past, which impacts the pollination patterns of key species like bees. Loss of habitat and diversity of flowering species have been factors in declining bee populations (alongside issues with industrial beekeeping like nutritional deficiencies, pathogens and exposure to pesticides and insecticides). Bees, alongside other pollinators including some wasps, birds, flies, beetles and butterflies are crucial to food production and declining numbers of pollinators will result in significantly reduced yields across many different crops.

Eeeep…So what can we do about it?

The good news is that while it is difficult (but not impossible) for us as individuals to influence policymakers, governments and corporations who have the power to enact the changes necessary to address the causes of climate change, there is much we can do in our own backyards to safeguard our garden ecosystems against these challenges. And if one backyard doing the right thing becomes a whole street, which becomes a whole neighbourhood, which becomes a whole region…well, that is how grassroots change happens!

Before we get stuck into the nitty gritty techniques to address the challenges explored above, it is worth mentioning that while they are both possible, it is easier to design a garden or whole property to be climate resilient from the start, rather than retrofitting an existing space. So if you’re just getting started and have a blank slate to work with, or you’re keen on climate-proofing your existing garden, we can’t recommend enough doing a Permaculture Design course (or getting your hands on some of the permaculture books we recommend below). The skills you will learn will be invaluable in understanding the existing ecosystem and weather patterns of your site, and designing a garden that will provide food, shelter and nourishment not only for you but for the wildlife and insect populations that need it too. That being said, here are *some* of the basic principles for creating a climate-smart food garden.

Observation

Observation is the key to good design, and therefore good gardening practice. Observing which plants, animals and insects are already on your site, as well as which plants seem to cope better than others in extreme weather events or drought periods, will give you essential information when it comes time to deciding crop selection, for example, as well as understanding how different species are being impacted by our changing climate.

Before you can figure out how to use water more efficiently in the garden, it helps to know how much rainfall you get, where it runs to, and where you could divert it to. Likewise, to understand which heat-sensitive plants may fare best during hot summers requires knowing which areas of the garden have afternoon shade, or the best place to plant a tree to provide that shade.

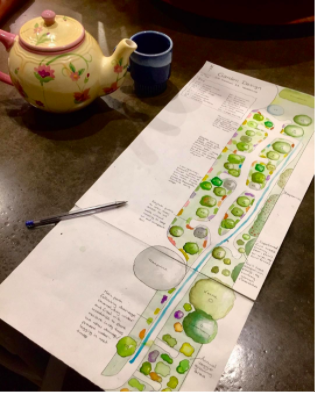

Start by sketching up a basic map of your garden, and spend as much time as you can taking note of:

Water: Rainfall patterns, where water flows in the garden, which areas drain well after rain and which get boggy or waterlogged? Do you have space for a rainwater tank, pond or other water catchment system? Where is your nearest water source? Answering these questions will help you to make the best use of scarce water in your garden, by planting water loving plants in the wettest areas, your drought tolerant herbs in the drier patches and so on.

Sun: Which areas of the garden get full sun year round, which get part sun and which are in shade all of the time? Note that the sun is lower in the sky in Winter, so shadows cast by buildings and trees will be longer. We can make use of existing shady areas to grow heat-sensitive plants, and keep the sunniest spots for our heat-loving summer veggies.

Wind: Which direction do the strong summer winds come from? How about the cold winter winds? Are there some spots in the garden that are more protected from wind than others? Many vegetable crops are sensitive to strong winds, which can damage plants and dry out the soil. Windy spots are a better place to dry your clothes than to place your veggie patch!

Vegetation: What plants are already growing on your site? If it’s an existing garden, make note of where trees, shrubs and other plants are already growing, and how they are faring. Noting the health of existing plants can help us understand if the conditions they’re growing in are favourable. If you’re working with a bare patch of grass or soil, check out what weeds are growing, as these can be great indicators of soil conditions (as well as guiding our decision making when it comes time to installing a new garden).

Wildlife: Which animals and insects do you have visiting or living in your garden? This information can help us design ways to invite native and beneficial species in, by providing suitable habitat, food and water sources, and how to keep pest species out.

Soil: Is the soil sandy, clay or silty? Sandy soils drain well but dry out quick, and leach valuable nutrients quickly. Clay is typically high in nutrients but can be prone to waterlogging, acidity and compaction. All soils can be improved with generous additions of composts, manures and mulch, which helps to improve water holding capacity and nutrient levels, boosts soil life and helps to store carbon in the soil.

Now that you’ve spent the time observing your garden space and understand the ecosystem that already exists there, we can get stuck into the principles and techniques that will help us address the challenges that climate changes poses. Read on in Part 2, where we will look at key strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate change in the garden, including:

– Water conservation strategies such as wicking beds and drought-tolerant crop selection

– Utilising organic matter to reduce methane emissions and cycle precious nutrients back into the soil

– Planting to attract endangered pollinators and beneficial insects

– Best practices for building healthy soil to increase plants ability to capture and store atmospheric Co2 in the soil

– Design strategies to protect plants from heat stress associated with rising temperatures

– Diversifying crop selection to increase resilience and yields, and the importance of perennial plants in the garden

Now that you’ve spent the time observing your garden space and understand the ecosystem that already exists there, we can get stuck into the principles and techniques that will help us address the challenges that climate changes poses. Read on in Part 2, where we will look at key strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate change in the garden, including:

– Water conservation strategies such as wicking beds and drought-tolerant crop selection

– Utilising organic matter to reduce methane emissions and cycle precious nutrients back into the soil

– Planting to attract endangered pollinators and beneficial insects

– Best practices for building healthy soil to increase plants ability to capture and store atmospheric Co2 in the soil

– Design strategies to protect plants from heat stress associated with rising temperatures

– Diversifying crop selection to increase resilience and yields, and the importance of perennial plants in the garden

Now that you’ve spent the time observing your garden space and understand the ecosystem that already exists there, we can get stuck into the principles and techniques that will help us address the challenges that climate changes poses. Read on in Part 2, where we will look at key strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate change in the garden, including:

– Water conservation strategies such as wicking beds and drought-tolerant crop selection

– Utilising organic matter to reduce methane emissions and cycle precious nutrients back into the soil

– Planting to attract endangered pollinators and beneficial insects

– Best practices for building healthy soil to increase plants ability to capture and store atmospheric Co2 in the soil

– Design strategies to protect plants from heat stress associated with rising temperatures

– Diversifying crop selection to increase resilience and yields, and the importance of perennial plants in the garden

Now that you’ve spent the time observing your garden space and understand the ecosystem that already exists there, we can get stuck into the principles and techniques that will help us address the challenges that climate changes poses. Read on in Part 2, where we will look at key strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate change in the garden, including:

– Water conservation strategies such as wicking beds and drought-tolerant crop selection

– Utilising organic matter to reduce methane emissions and cycle precious nutrients back into the soil

– Planting to attract endangered pollinators and beneficial insects

– Best practices for building healthy soil to increase plants ability to capture and store atmospheric Co2 in the soil

– Design strategies to protect plants from heat stress associated with rising temperatures

– Diversifying crop selection to increase resilience and yields, and the importance of perennial plants in the garden

Recent Comments